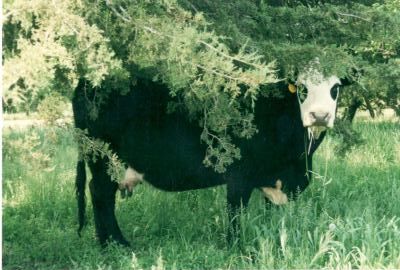

A cow catches some shade on the farm.

A cow catches some shade on the farm. Dad played a small fly-specked, white Braun radio to help calm the cows in the barn. During summer flies got caught in jars in the window or between window panes and drove a person nuts with the wild, erratic buzzing as they hit the sides trying to escape.

Flies also attacked the cows. At a young age my first job in the barn was holding the cows’ tails so they wouldn’t swish in Dad’s eyes while he milked. Cows combated the sting of flies with their hairy tails.

I found it fascinating to see the skin ripple on their rumps and sides from the bites they were not allowed to ease. Sometimes the cow won, stinging my fingers as the course tail whipped from my grasp.

I then took pleasure in the clean work of measuring sweet-smelling feed for the cows and enjoyed the fragrant scent of molasses mixed with soybeans and corn. I placed the grain in the trough before each stanchion, which locked behind the cow’s head.

Dad used obvious nomenclatures for some of the cows, such as “Kicker,” “Little Teat,” Big Teat,” Dynamite, and “Little Dynamite.” With care, we slapped “kickers,” or hobbles with metal chains that hooked onto the cows’ bony knees, onto a few of the uncontrollable bovines.

Around age seven, I was big enough to milk the cows. That meant I was also able to scrape the pungent urine and manure into the gutter. We shoveled that stinky ooze out the door after the cows left the barn.

A hole that never dried up, even in the heat of August, putrefied near the barn door where the concrete stopped. As a young girl, my sister viewed it as bottomless. She entertained nightmares of falling in and getting sucked under as though the pit held rancid quicksand.

In winter the frozen deep ruts of the corral hardened to the consistency of rock, and as sharp as glass on legs without protection. During spring and fall rains, our buckled, rubber overshoes squished, slurped, and sucked with each step of the oozing goop.

Once in a while the foot raised and the boot stayed down. The feed trough seemed to shrink on occasion. An illusion, the sludge just deepened.

By the time I hit eleven or twelve, we no longer poured milk into the cream separator or slopped the hogs with skimmed milk. The milking turned quite automated. We placed the teat cups near the cows’ udders. The cups suctioned on, and the milk traveled through rubber tubing into pipes that carried it to the stainless steel bulk tank.

A blade in the center of the tank churned the milk so the cream didn’t separate, and a thermometer gauged the refrigeration.

Dad expanded the milking to fifty cows and sold the grade-B milk to the Orchard Cheese Factory. A truck arrived from Orchard a couple of times a week to empty the tank. Mom cleaned the bulk tank then, but during my high school summers, I inherited the job. I scraped, hosed, and washed.

To this day I abhor the smell of warm milk. At least the smell of sour milk surpassed that of the chicken coop or the hog shed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed